Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana

The Union Cabinet chaired by the Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi approved a New Crop Insurance Scheme on 13th Jan 2016 aimed at providing maximum insurance for farmers at minimum premium.

Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (Prime Minister Crop Insurance Scheme) in which the premium rates to be paid by the farmers have been brought down substantially so as to enable more farmers avail insurance cover against crop loss on account of natural calamities. The scheme will come into effect from the upcoming kharif season.

Under the new Crop Insurance Scheme the farmers premium would be 2% for kharif foodgrains and oilseeds crops and 1.5% for rabi foodgrains and oilseeds crops. For horticulture and cotton crops the premium has been fixed at upto 5% for both khairf and rabi seasons.

There is no upper limit on Government subsidy. Even if balance premium is 90%, it will be borne by the Government. Earlier, there was a provision of capping the premium rate which resulted in low claims being paid to farmers.

The New Scheme aims to enhance insurance coverage of crops up to 50% of the total crop areas from the existing level of about 23% over the next 2-3 years. It also provides for change in criteria to determine crop losses by providing local level assessment for calamities like hailstorm etc.

Under the new scheme simple technology through phone and remote censors would be used for quick estimation and early settlement of claims. Crop Insurance portal will be used extensively to ensure better coordination and transparency.

The Government’s liability on premium subsidy will be shared by the Central and State Governments on 50-50 basis.

The Government will substantially increase budget for crop insurance from Rs. 2883 crores in 2015-16 to Rs. 7750 crore in 2018-19

The New Crop Insurance Scheme will be implemented by private insurance companies along with the Agricultural Insurance Companies of India Ltd.

Analysis

Agriculture in India is highly susceptible to risks like droughts and floods. It is necessary to protect the farmers from natural calamities and ensure their credit eligibility for the next season.

India has experimented with many schemes for crop insurance like Comprehensive Crop Insurance Scheme, Farm Income Insurance Scheme, National Agricultural Insurance Scheme of 1999-2000.

But the continued cases of farmers suicide indicate a gap between the present schemes and need of farmers.

1) States with Low Insurance Cover (Source: Crop Insurance officials)

– Punjab, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Western Uttar Pradesh

– Farmers here don’t have any knowledge about insurance and remain without cover

– Small farmers have no incentive as they have to pay the premium

– In many cases farmers have written to banks saying they do not want insurance

– The banks have complied with such requests to meet targets although insurance is a compulsory feature of agricultural loan schemes

What the Experts Say:

– The government needs to legislate on the subject, making insurance cover compulsory The government should pay the premium for small farmers

– Holding agricultural as well as bank officials accountable for process pertaining to crop insurance should also be a part of the legislation

2) States with High Levels of Insurance Fraud (Source: Crop Insurance officials)

– Maharashtra (Aurangabad and Jalgaon), Gujarat (Saurashtra), Andhra Pradesh (Rayalaseema), Karnataka (Dharwad and Haveri), Tamil Nadu (Nagapattinam and Sivaganga) and Telangana (Mahbubnagar)

– Coverage in these regions is high and so is fraudulence

– In some districts hundreds of farmers are literally living off fraudulent claims

That farmers have to pay the premium has met with a backlash in multiple states with several farmer associations even writing to insurance companies to not debit the insurance premium. Given that the banks are under pressure to meet targets for the Kisan Credit Card (KCC), they decide to waive off the premium component.

These schemes have also broadly cleaved India into two parts with one set of states, which are under-penetrated , reporting lack of awareness among farmers about insurance even as multiple frauds are being reported from the second set of states that have better coverage.

Source: ET

Boosting Water Transport in India

The Union government is working on a strategy to increase the movement of goods and passengers through waterways by nearly five-fold from a mere 3.5 per cent now to 15 per cent by 2019, Union Shipping and Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari has said. He was addressing a conference at ASSOCHAM.

The Minister said the Shipping Ministry had prepared a vision document on coastal shipping, tourism and regional development to increase the share of inland water transport and coastal shipping, development of regional centres to generate cargo for coastal traffic and promotion of cruise tourism.

To encourage transportation of goods by coastal shipping, service tax has been brought on par with road and rail transport. The government has also relaxed cabotage (right to operate transport services within a particular territory) for specialised vessels like Ro-Ro, Hybrid Ro-Ro, car carriers and truck carriers for a period of five years.

On port development, Mr.Gadkari said the government had taken a decision to start three major ports at a cost of Rs.18,000 crore to Rs.20,000 crore. These include a port at Wadhwan near Dahanu in Maharashtra, Colachel Port near Kanyakumari and the Sagar Island Port in West Bengal.

The Wadhwan Port will be built as a joint venture between JNPT and the Maharashtra Maritime Board, and was intended to decongest the overburdened JNPT Port at Nhava Sheva.

Analysis

For decades India has failed to develop 14,500 kilometers (9,000 miles) of its inland waterways as a viable alternative to move cargo and ease congestion on land.

There is acceptance that transportation by waterways, both coastal and inland, is fuel efficient, environmentally friendly and more economical than rail or road, the share of goods transported via India’s inland waterways is only 0.4%, compared with 42% in the Netherlands, 8.7% in China and more than 8% in the US.

The transportation cost for inland waterways is Rs.1.06 per tonne per kilometer, while it is Rs.2.58 for highways, according to the Indian ministry of shipping.

The development of waterways would reduce the logistics cost, enabling India to effectively compete in the international market.

The Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) came into existence on 27 October 1986 for development and regulation of inland waterways for shipping and navigation. The Authority primarily undertakes projects for development and maintenance of IWT infrastructure on national waterways.

The government presented legislation in May that would grant the government rights to regulate and develop 101 channels across 24 states for shipping and navigation, in addition to the existing 4,382 kilometers of five main waterways.

Of the five national waterways India declared since 1986, three are operational. Development has lagged behind other modes of transport in the absence of integrated policy, insufficient financial outlays, lack of expertise and coordination with states. While proposals to link major Indian rivers and facilitate commerce and manage water date back to British colonial days, the plan has remained just that.

Source: Livemint

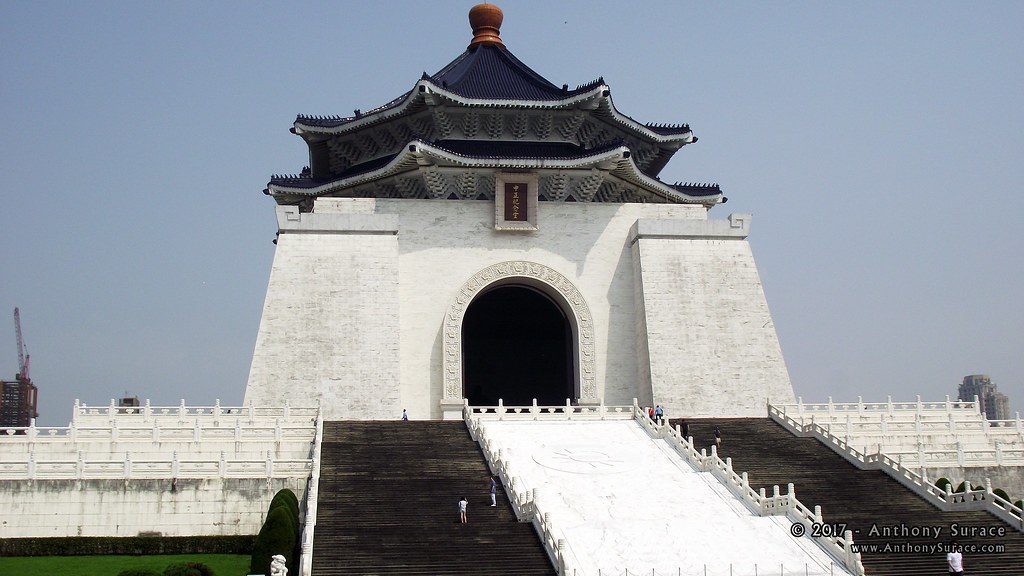

Namame Gange Project

The Central government will be setting up a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) for its ambitious programme Namami Gange or Clean Ganga initiative.

According to official sources in the Ministry of Water Resources, after deliberations with various stakeholders, it was found that an SPV on the lines of the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC) would be best suited for the project.

he Chief Secretaries of all States through which the Ganga passes will be made members of the board of this SPV, as would select municipal commissioners of big cities on the Ganga route.

As of now, the Clean Ganga project involves the Ministries of Water Resources, Urban Development, Environment and Forests, Roads and Highways and Rural Development and Sanitation. A major conference called Jal Manthan will be called in February to discuss all these issues, and to carve out a special plan for the Ganga, within a larger water policy for other rivers.

Analysis: Cleaning the Ganga

It isn’t walking on water, but still a very difficult job – one that India has been trying unsuccessfully to accomplish for the last three decades. .

Much of the effort to clean the Ganga over the last 30 years has been centred around creating sewage treatment capacities in major urban centres along the river. Besides the fact that a lot of this capacity has remained underutilised or non-functional, the discharge of urban sewage is only one of several interventions required to rid the holy river of pollution.

The government’s Namami Gange programme seeks to tackle the problem at several levels at the same time. “Rejuvenation†of the Ganga includes reviving ‘Aviral Dhara’, or continuous flow in stretches that have gone dry due to natural or man-made reasons, regenerating the river ecology, making the river an important inland waterway, reviving it as a habitat for dolphins and gharials, and spreading awareness about the need to keep the Ganga clean.

1) Treating Urban Sewage – Creating sewage treatment plants (STPs) was at the core of the Ganga Action Plan that began in 1985. About 1,000 million litres of sewage treatment capacity per day was set up, but lackadaisical state governments and lack of maintenance by municipal authorities have kept a large part of this capacity on paper alone.

The government has now decided to rope in corporates to do this work in all the 118 urban centres along the river. Companies will have to create additional capacities, use existing capacities at optimum levels, and operate and maintain the facilities for a minimum 15 years to produce treated water at prescribed standards.

2) Rural Sewage – About 1,650 gram panchayats lie directly on the banks of the Ganga. The sewage they generate is almost entirely untreated. About half the population in these villages defecates in the open. The government plans to use biological means to deal with this waste. It wants to experiment with a model said to have been used in a Punjab village by a local spiritual leader, Baba Balbir Singh Seechewal, who is credited with the successful cleaning of the Kali Bein river with public participation.Seechewal is supposed to have inculcated the practice of segregation of solid and liquid waste, treatment of waste water through oxidation ponds, use of treated water for irrigation, and composting of solid waste. He is said to have infused a sense of community participation and ownership of the river.

3) Industrial Effluents – There are 764 grossly polluting industries on the banks of the Ganga, mostly in Uttar Pradesh. These include tanneries, paper and pulp industries, sugar mills, dyeing factories, distilleries, and cement plants. Effluents from all these flow untreated into the river. Tanneries near Kanpur alone generate about 25 million litres of effluents daily.

These industries have been repeatedly told to set up common effluent treatment plants (CETPs), install new technologies, and ensure zero liquid discharge into the river. But enforcement has been lax.

4) Surface Cleaning – Solid waste, clothes, polythene, and all kinds of religious offerings are dumped into the river, and float on its surface. It is the easiest to clean them – and can result in a quick visual makeover for the river.

Machines called trash skimmers have been ordered from abroad to clean the river surface near all major towns. One of these skimmers is already operating in Varanasi.

5) Burning the Dead – Cremation along rivers and immersion of remains is a unique reason for pollution in Indian rivers, and especially the Ganga. Burning of wood leads to air pollution as well. One of the efforts in the Ganga Action Plan of 1985 was to build gas or electric crematoriums, especially in religious centres like Varanasi and Allahabad. Not much was achieved, however.

Several other initiatives would be required include the launch of a public awareness exercise, regeneration of aquatic biology, plantations, and riverfront development.